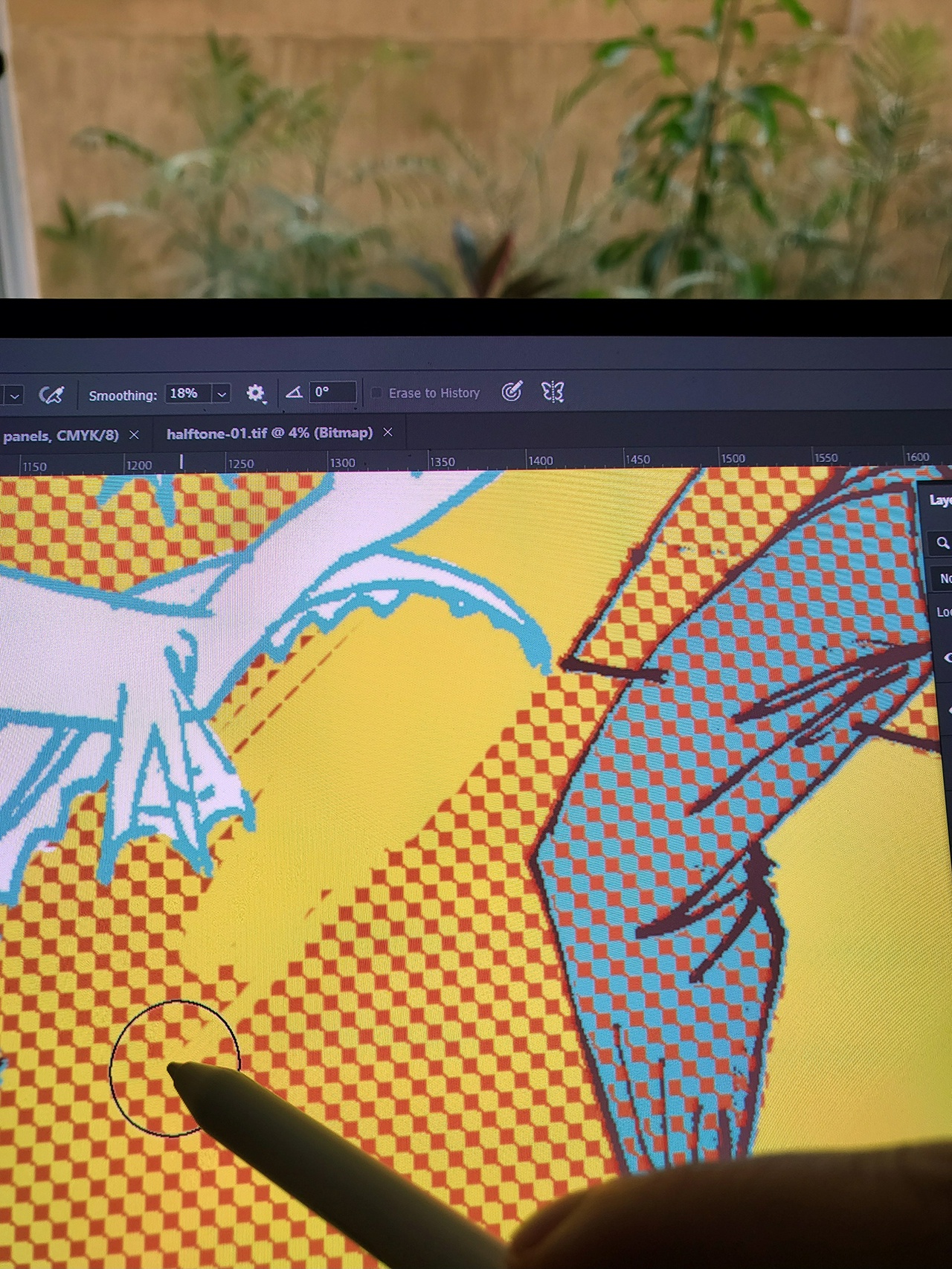

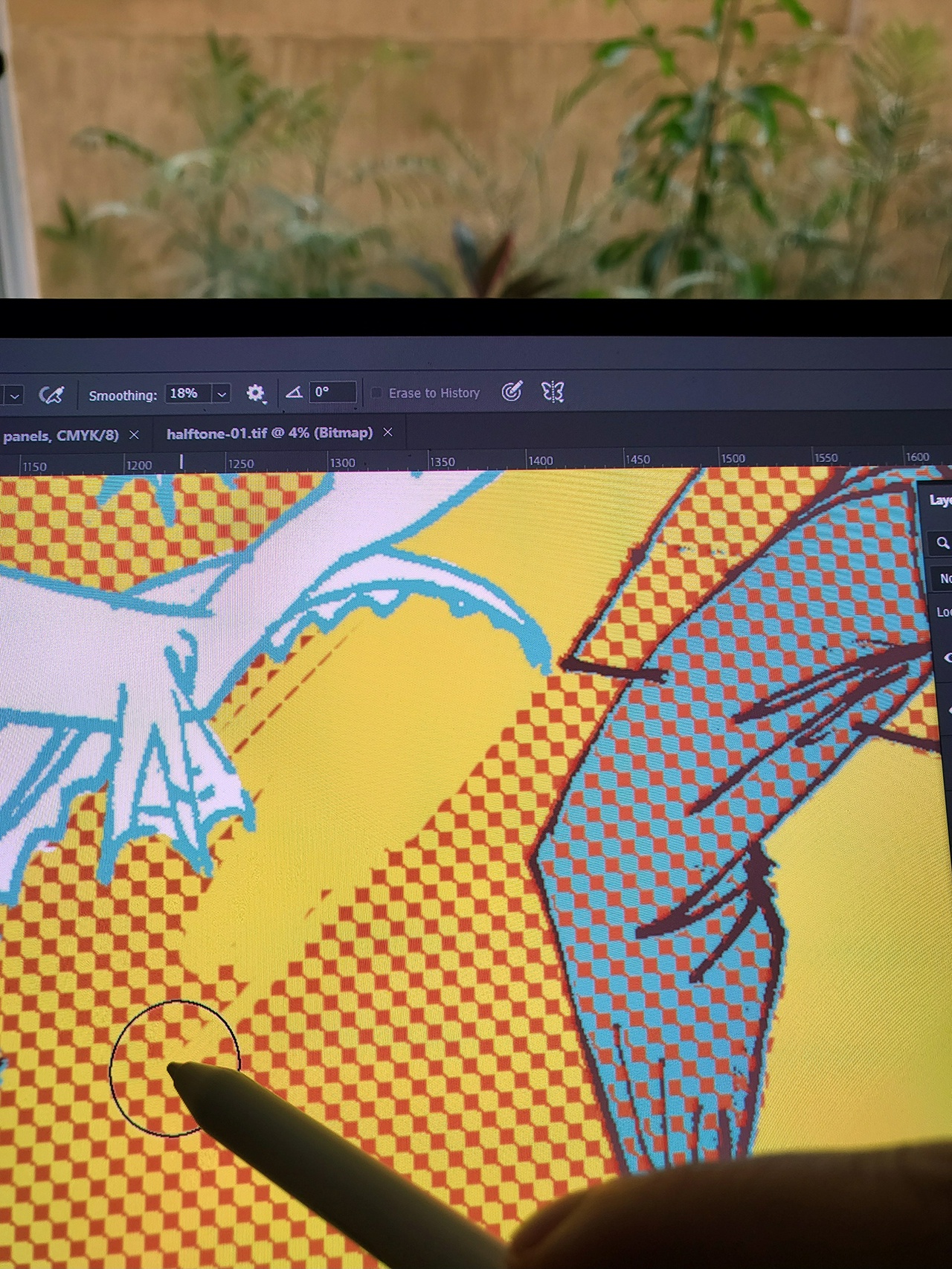

6 pages to color and 33 to letter.

Lettering moves pretty quickly, but digital coloring is slow and loathsome. So many hours sat in front of a computer screen which makes me feel like a zombie at the end of each day. Can't wait to be done with this part already.

Started reading Kazuo Ishiguro's NEVER LET ME GO sometime ago, which started interestingly enough but I largely lost interest by the last third of the book and now find myself winding most evening's down with a film instead. This however is also likely due to the above-mentioned zombie status induced by long hours at the computer desk.

Today's screening: LOST HIGHWAY

#journal #work #comix #TSG

Happy to see the fine folks at the Letterform Archive in San Francisco celebrate 10 years of typographic awesomeness. To celebrate, they asked a number of designers to contribute a “1” to use in conjunction with their circular AAAAAAAAA logomark to signify a “10”.

Figured I'd pitch in with the most intuitive “1” in human history, based on a photo of my own hand.

#work #journal

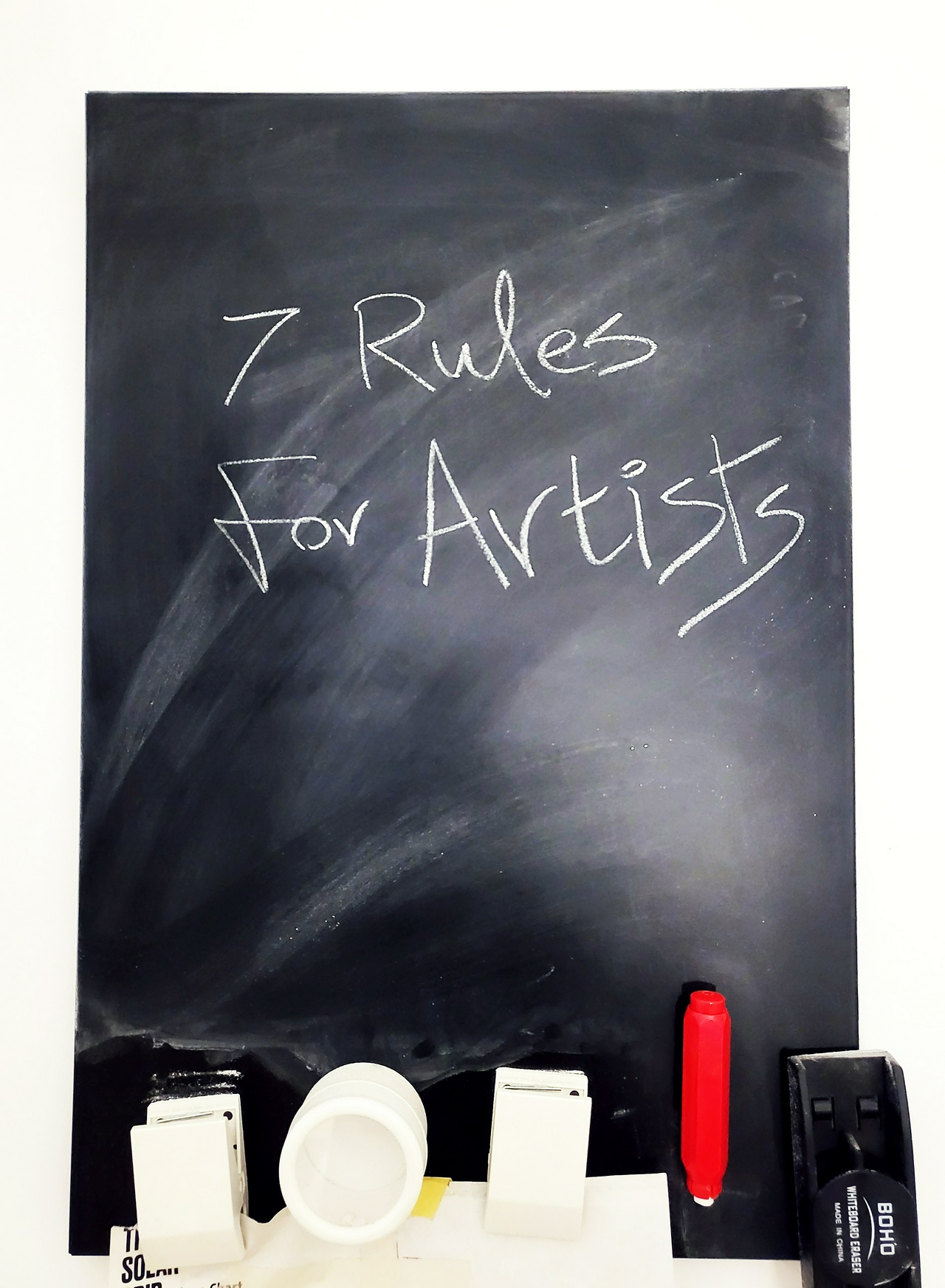

Issue #226 of the RESTRICTED FREQUENCY newsletter dropped a few days ago. In it we discuss 7 Rules for Artists.

Sign up lives here.

#rf

Inking is done.

Tones, touch-ups, and colors where they apply remain before moving onto lettering.

Lords help me.

#TSG #work #comix

9 pages worth of inks to go.

#TSG #Comix #Work

8:30 am. Garden kittens have stormed the house and laid claim to my bed, ruffling around playfully between the sheets. I haven't the heart or energy to chase them out. Fresh coffee in hand fails to disperse sleep from my eyes as a I plan the day ahead:

Tomorrow I need to finish most of the branding work on PROJECT FUNNYCULT, run a couple errands, including a much-dreaded Ikea run. I'd really hoped to avoid Ikea upon the move to Cairo, which I hoped to avoid upon the move to Cairo, but I don’t have the time or patience to comb through the city’s endless shopping clusters for a couple of basics. A negligible betrayal only if it were my first since being here.

RESTRICTED FREQUENCY #225 goes out around midnight. Its title: Anything But The Art! 😱

#journal #work