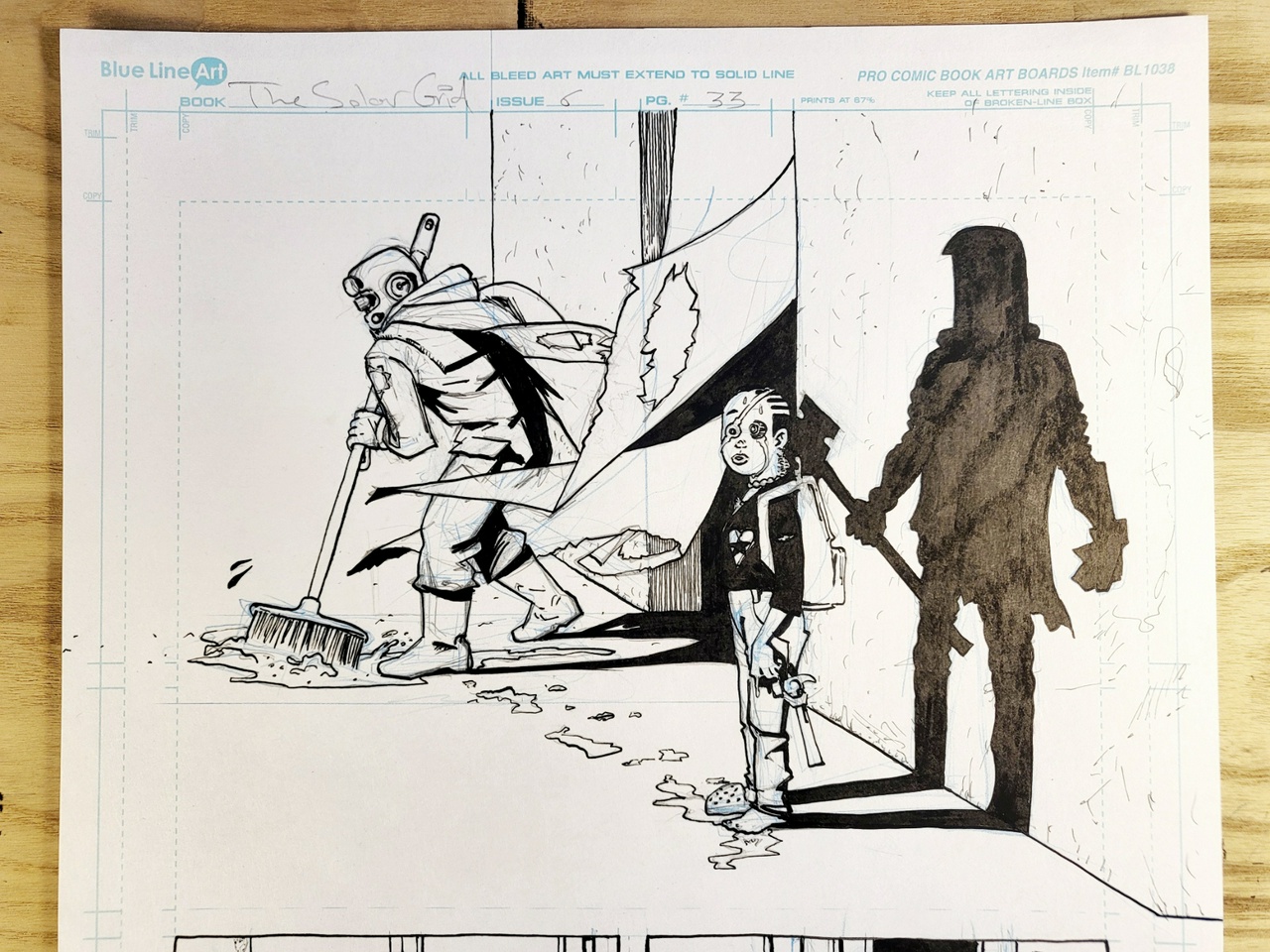

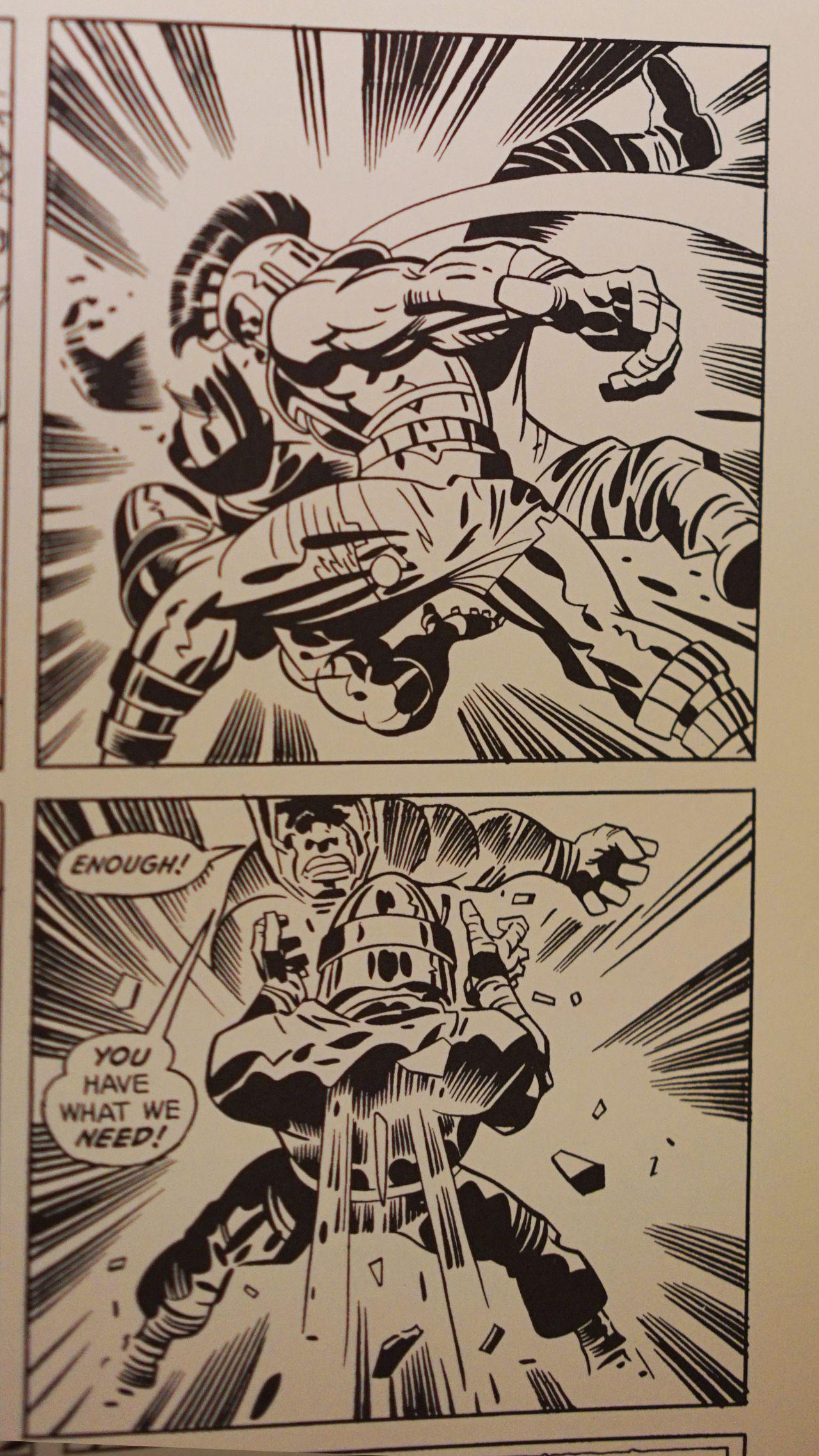

Good gods, I've waited the better part of 7 years to draw this godforsaken panel. Would have loved to get to it while Steve was still among us. Though I'm not too sure how he would've felt about it. But I do hope he's cool with it now, wherever he is.

This, from Joe Biel's MAKE A ZINE, is new to me:

“Simultaneously in New York City, in a parallel world to the Beats, sci-fi fans, and West Coast hippie comix artists, was a teenager named John Holmstrom. Homstrom was a student at the School of Visual Arts who approached the dean and demanded a cartooning program. After his demand was met and world-famous cartoonists Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner were hired, Holmstrom dropped out and began working for Kurtzman and Eisner. Next Holmstrom did what any respectable twenty-something would”. He was, for the record, twenty-one. “In 1975 he created a national zine about the infant music movement that he and his friends were involved with.”

That zine was called PUNK, and as such christened the name that would be associated with the genre of music birthed out of that burgeoning scene.

“The inaugural issue featured an impulsive cover feature about The Ramones and a hilarious interview with Lou Reed.”

This connection between Punk and Comix—or Cartooning if you will—is new to me. In fact the connection is double pronged; Not only would the Kurtzman/Eisner-trained Holmstrom define the genre through his zine, but also through his later record-sleeve art for albums by The Ramones.

The connection is even stronger still, given that comicbooks themselves were birthed out of zine culture. After all, prior to the creation of Superman, Joe Schuster and Jerry Siegel produced two zines: TIME TRAVELER and SCIENCE FICTION. Superman himself was conceived as a science fiction strip, but after failing to get any interest from the newspaper syndicates (considered the “proper” gatekeepers of the medium at the time), their only viable option was to put the work out in what was thought to be the “less-sophisticated” comic-book form, published through a company that had only been around for a mere four years* with the bulk of its output penned by the guy who founded it, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson who also wrote for the pulps (many of which shared their DNA with zine culture, especially compared to the more “professionally”-produced “slicks”).

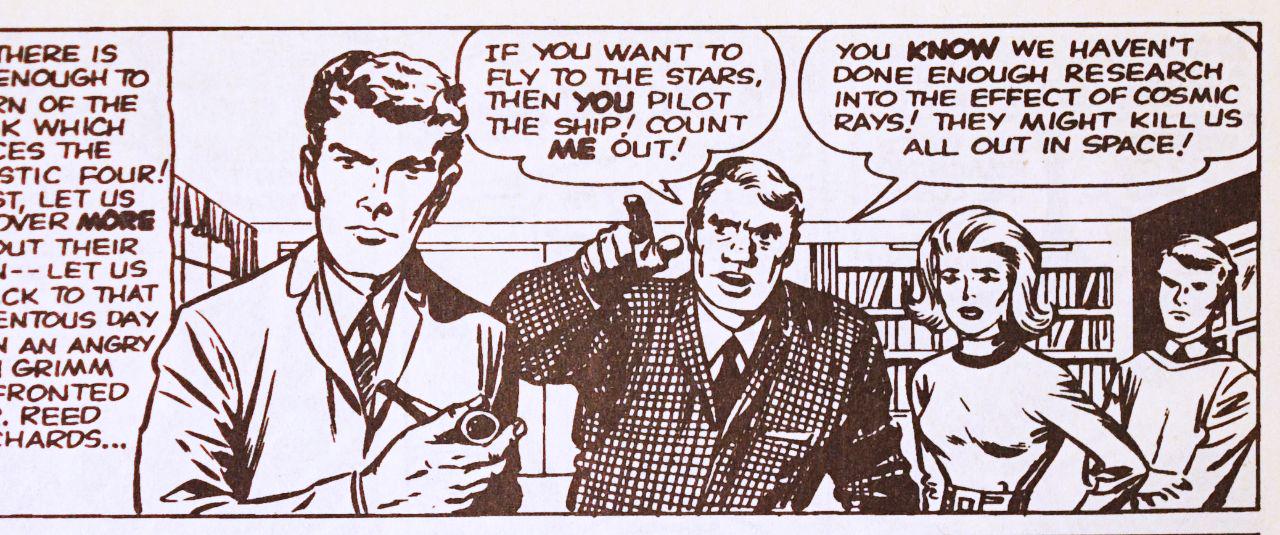

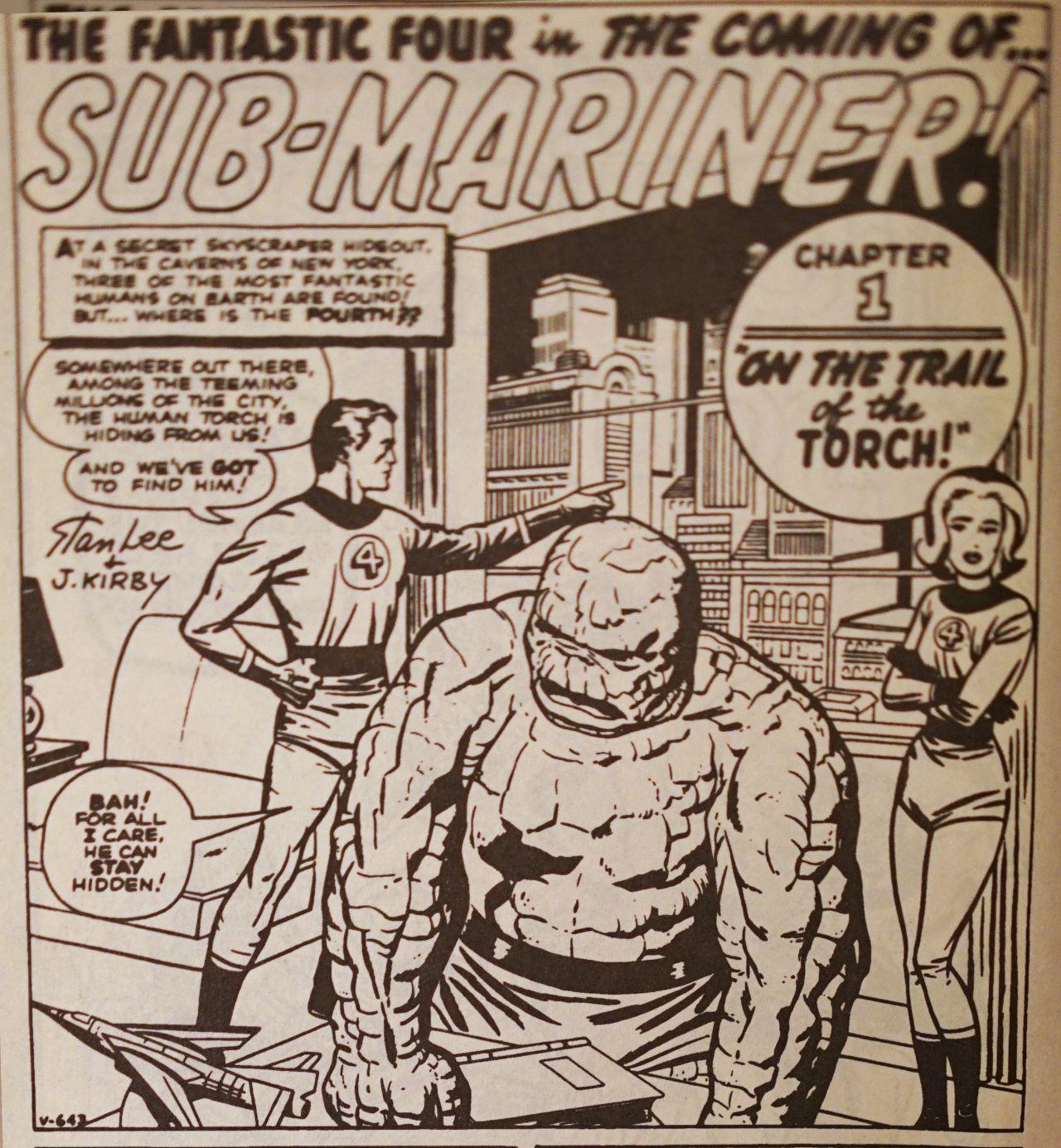

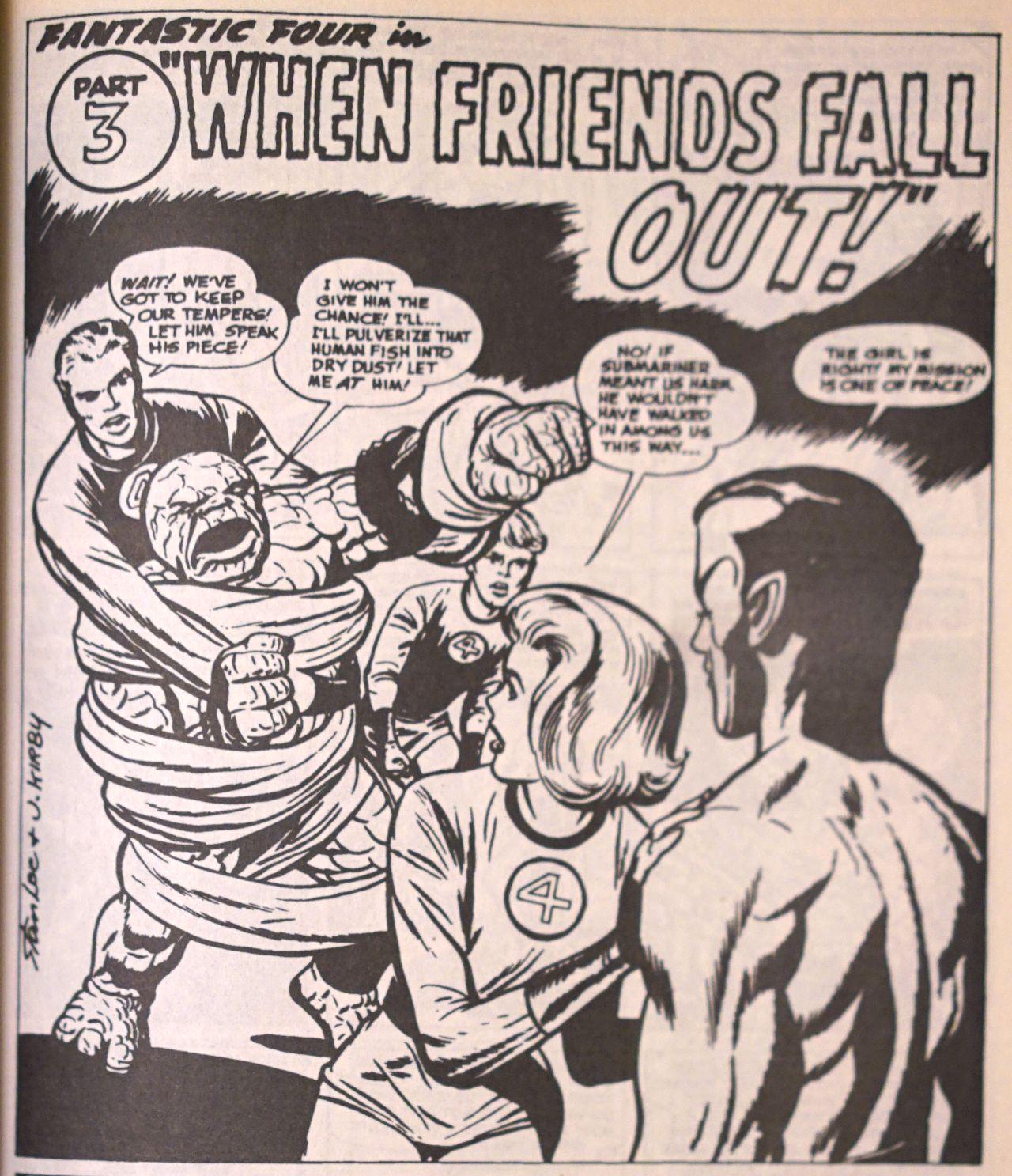

Fast forward a few decades after Superman's National Periodical Publications becomes the biggest producer and distributor of comic-books across North America, three guys get together (Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Steve Ditko) and begin to put out one comic-book anthology after the next (the ideas of which all stem from science fiction) with far more personality and eccentricity than the cookie-cutter corporate stuff produced across the street and in so doing kick off “the Marvel Age of Comics”. What they created may not have been zines per se, but the approach to making the stuff had way more in common with zines than with the decision-by-committee method dominating comicbook corporations today, or heck National/DC at the time. Three dudes making shit up and interacting with their growing readers in the back pages? Sounds like a zine to me, with the single most significant difference being that they had the backing of a single financier who made his coin in the pulps.

A few years later, the underground comix movement would be kickstarted by Robert Crumb's legendary ZAP COMIX, sold on Haight/Ashbury out of a baby stroller. Most definitely a zine.

This inspires a 24-year old “hippie” in Milwaukee to start Kitchen Sink Press and publish other underground cartoonists before reviving Will Eisner's creator-owned THE SPIRIT and reintroducing it and its creator's pioneering genius to a whole new generation. (Eventually, the medium's most coveted award would be named after him.)

Five years later across the Atlantic, a music rag in London called SOUNDS (largely known for covering the rising punk scene) begins running a comicstrip by two art students: Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy. One of them would go on to leave his mark on America's two top comicbook corporations and the other would eventually end up co-creating MAD MAX: FURY ROAD. One year after Milligan and McCarthy's stint at SOUNDS, the magazine runs a strip by another young cartoonist by the name of Alan Moore.

One year later back in America, Francoise Mouly and Art Siegelman publish a comix anthology zine using a printing press set up in their residential loft. The hands-on approach to production allows them to experiment with binding, include stickers, and intentionally torn pages. They call it RAW and in its pages Spiegelman runs an odd-looking comix series about the holocaust that involves anthropomorphic animals. It is titled MAUS, and within 12 years becomes the first and only “graphic-novel” to win America's prestigious Pulitzer prize.

A couple years after RAW hits the scene, two Latino punks(!) out of southern California send their self-published zine to a comics journalism magazine (the majority of its content at the time written by the publisher himself) that literally started as an adzine. Hoping to get reviewed, they are instead offered a publishing deal, and LOVE & ROCKETS #1 is published and thus the mighty Fantagraphics is born (also, note the nod to sci-fi in “Love & Rockets”).

Two years later, a couple guys in New Hampshire get together and put out a very amateurish-looking black and white comicbook (practically a zine) filled with unhinged eccentric energy, evident even in the title: TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES.

Two years after that a comicshop owner in Oregon starts a black and white comics anthology called DARK HORSE PRESENTS. Many years later, it's where Mike Mignola's HELLBOY and Frank Miller's SIN CITY make their first appearance.

Looking at the comix landscape today, it would seem that comicbooks are for the most part a corporate affair, the drive of which is purely capitalist with little to no substance. Examine history carefully though and it becomes evident that the DIY outsider energy we typically associate with zines and punk, combined with the visionary imagination we ascribe to science fiction, is what creates the special sauce that is the lifeblood of the comix medium.

(*) I lie a little, the history is somewhat more complex than that. Siegel and Shuster did indeed create strips for the Major's publications (Henri Duval, Doctor Occult, and Slam Bradley to name a few) but noticing Wheeler-Nicholson's shoestring operation and inability to make prompt payments, they decided to sit on Superman for a better opportunity, which came in an offer from M.C. Gaines and his plans to produce a weekly comics tabloid thing (so, closer in format to Sunday strips seen in the newspapers, considered the far more legitimate approach to engaging with the medium). Gaines' publication however never materialized, and he was approached by Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz who had bought Major Malcolm's operation and sought to utilize it with their hold on magazine distribution which they attained through mob and gang connections. They were planning to produce a new regular comic book and asked Gaines if he had any material for it. It was called ACTION COMICS, and the strip Gaines gave them was the first official installment of Superman (I say official because Siegel and Shuster had toyed with proto-Superman ideas well since high school, the first of which might have been the illustrated short story THE REIGN OF THE SUPERMAN published in issue #3 of their SCIENCE FICTION zine, circa January 1933).

(The last one isn't pointing, and it's from late stage Kirby's

(The last one isn't pointing, and it's from late stage Kirby's

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last example from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last two examples from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last two examples from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last image from from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Last image from from late stage Kirby's SPIRIT WORLD.)

(Photo via

(Photo via